By Lily Dayton for UC Santa Cruz

In the spring of 1948, UCLA graduate student Ken Norris was eager to return to his field research site in the Coachella Valley, where he’d spent previous seasons crouched in the sand dunes, observing the desert iguanas that scurried beneath the Dicoria bushes. When he arrived at his research plot, however, he encountered a foreboding sight: survey stakes impaling the desert floor. The next time Norris returned, more than half his research site had been planed down to flat sand. The Dicoria bushes—and the desert iguanas they had sheltered—would soon be replaced by a motel complex. Norris’s research project was forced to an early end.

“The catastrophe of the desert iguana study plot shook loose in me a clear and somber vision of the future of wildland America,” Norris wrote in his posthumously published memoir Mountain Time (2010). “No question about it, the rapidly urbanizing United States would soon be a place where the natural land and its life would be embattled nearly everywhere.”

Norris’s thesis advisor, zoologist Ray Cowles, also lamented the loss of these wildlands where he’d conducted research and trained future scientists. Cowles had even tried to persuade the University to adopt natural areas for the purpose of teaching and research—but his efforts were futile.

Along with unprecedented population growth and urbanization, the post-World War II era marked a paradigm shift in university science programs. With technological advances stemming from the war effort, research institutions prioritized “big science,” exclusively funneling support toward the physical, molecular, and biomedical sciences. Norris and Cowles watched as traditional field-based sciences began to fall by the wayside.

Developing the Natural Reserve System

After Cowles had retired in the early 1960s, Norris was an assistant professor at UCLA and resumed Cowles’s efforts to establish a system of University of California (UC) protected natural areas. The University had already acquired field stations under the tenure of then-President Clark Kerr. But these scattered areas represented only a sprinkling of California’s diverse ecosystems. Norris thought the University could play a vital role in preserving a more complete representation of the state’s natural diversity by creating a systemwide network of reserves because, as he put it, “you can't study nature without a nature to study.”

Norris brought a proposal created by senior faculty to President Kerr and by January of 1965, the UC Regents established the Natural Land and Water Reserves System, eventually renamed the Natural Reserve System (NRS). The approval allowed Norris to explore California's vast wildlands to survey potential reserve sites. He reviewed 81 sites, 13 of which were initially incorporated into the NRS.

Roger Samuelsen, the first NRS director, credits Norris as a great visionary. But equally important, he says, was Norris’s warm, open demeanor.

“I think much of his success was that he had a way of bringing others into the fold,” Samuelsen explains. “He could motivate people; he could get them not only involved but get them as enthused as he was. And I think that's because he was such a real, upfront, very articulate person.”

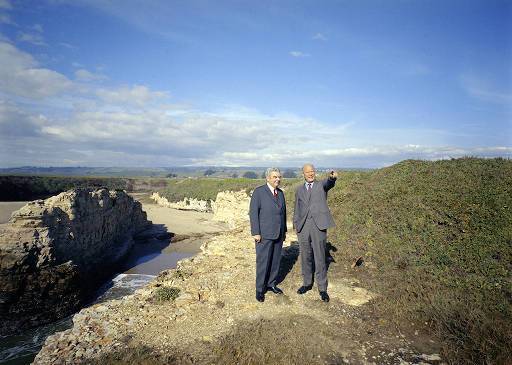

UC Santa Cruz Chancellor Dean McHenry with Donald Younger, donor of Younger Lagoon Reserve, in 1973. Image courtesy Special Collections, UC Santa Cruz.

Samuelsen emphasizes that the support of UC leadership was—and still is—instrumental to the success of the NRS. “Obviously, the initiative of Norris and the committee was very important, but without the support of President Kerr, without his acknowledgement and recognition of the importance of this initiative, it never would have happened.”

In 1972, Norris moved to UC Santa Cruz as a professor of natural history. During his first few years, he co-founded the Long Marine Laboratory and the Institute of Marine Sciences. The land and lagoon used for the research campus was donated by Donald and Marion Younger, whose family had owned a ranch for over a century—establishing the first UC Santa Cruz natural reserve, officially incorporated into the UC-wide NRS in 1986.

The Natural Reserve System today

From humble beginnings, the NRS has grown to encompass 756,000 acres across 39 reserves, making it the largest university-administered reserve system in the world. The reserves protect a diverse assemblage of California’s native grasslands, deserts, conifer forests, oak woodlands, coastal wetlands, chaparral, sagebrush and other distinct habitat types—along with the multitude of species these habitats support.

Today, the UC Santa Cruz Natural Reserves comprise over 10,000 acres of pristine land on five sites that fringe the Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary. From the rocky island habitat of Año Nuevo Natural Reserve to the coastal wetlands of Younger Lagoon Natural Reserve, the maritime chaparral of Fort Ord Natural Reserve, the redwood forests of Landels-Hill Big Creek Natural Reserve, and the wooded hills of the Campus Natural Reserve, UC Santa Cruz Natural Reserves offer living laboratories with diverse ecosystems for scientists and students to learn about the Central Coast in perpetuity.

Accessibility

Each year, tens of thousands of researchers, university students and public school students, as well as members of the general public, use the Natural Reserves’ living laboratories and outdoor classrooms to conduct field studies, teach, and learn. Besides providing a protected natural ecosystem in which to set up a research project, many of the reserves offer features to ease the logistics of field research, such as research housing and laboratory facilities.

In addition, many reserves are situated near UC campuses, allowing researchers to conduct studies with minimal travel time. For example, Younger Lagoon Natural Reserve protects 75 acres on UC Santa Cruz’s Coastal Science Campus, providing field research opportunities literally right outside classroom and office doors.

Only a 30-minute drive to the north, Año Nuevo Island Natural Reserve dedicates 25 acres within State Park land to scientific research, including studies of pinniped colonies, nesting seabirds, and native plants.

“The close proximity of Año Nuevo Island to UC Santa Cruz makes it an ideal location for a faculty member to carry out research, but, more importantly, for graduate students to be able to do research,” says Dan Costa, professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at UC Santa Cruz. He explains that the convenient locale allows graduate students to conduct research during the semester, without having to give up coursework or teaching opportunities.

Costa adds that without the reserve, he would have to travel to the Antarctic or the Galápagos Islands to conduct much of his marine mammal research.

Long-term research

Because reserves are protected in perpetuity, they make long-term data collection possible, allowing researchers to track ecological changes resulting from factors such as disease or climate change over time.

“Having a network of reserves across the state makes it possible to document change at any one site or across these environmental gradients that California is full of,” says Erika Zavaleta, professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at UC Santa Cruz. In her research looking at wildlife response to climate change, Zavaleta is grateful to have access to decades of historical weather data collected at the reserves.

Through long-term studies at Fort Ord Natural Reserve, which shelters a high number of rare and endemic plants, researchers are examining how species interaction and climate patterns affect the persistence of threatened and endangered plants. Long-term data collected at Landels-Hill Big Creek Natural Reserve help scientists understand the ecology of redwood trees throughout their range, as well as how to conserve and manage steelhead populations throughout the state.

Experiential learning

Zavaleta points out that the same factors that make the reserves attractive for researchers—such as easy access to a natural, intact ecosystem—make them ideal for teaching field courses.

“We do a lot of inquiry-based research with students,” she says. “Students generate the questions and then we help them through the whole process of figuring out their experimental approach, collecting their data, analyzing it, and communicating their results.”

UC Santa Cruz has been a leader among schools that utilize and contribute to the NRS—which isn’t surprising; it’s where Ken Norris created the renowned Natural History Field Quarter, a course that takes students into the field for a quarter-long expedition to reserves across the state. Field Quarter is still popular on campus today and is now one of six intensive field courses offered at UC Santa Cruz.

“I think we as a campus are increasingly known as the campus that is really into field experiences and experiential learning,” says Costa, adding that Norris’s legacy lives on in this field-based approach. “And I think that's a legacy to be proud of, and one that we're continuing to develop.”