Monterey larkspur. Pluman ivesia. Hoover’s manzanita. Payson’s jewelflower. Never heard of them? Few others have, either. They’re among California’s most vulnerable plants—rare, found in just a few spots, or extra finicky about where they will grow.

Lucky for them, these and about 370 other vulnerable native plant species are found within the UC Natural Reserve System (NRS). An expansive new study finds the NRS is key to protecting the Golden State's most vulnerable plants now and in the future. While the analysis predicts climate change will have a searing effect on plant conservation across California, the expertise of NRS scientists and other land managers can help shelter these jewels of biodiversity against extinction.

To biologists, vulnerable plants are canaries in the coal mine of climate change. Limited to certain soils or weather conditions, few in number because they have specialized habitat requirements or have been uprooted by California’s large human population, these rarities will be among the most challenging to preserve over the long run.

The complications of climate change

"The concern is with climate change, plants with more restricted ranges have narrower climatic tolerances and therefore may be more prone to habitat loss or local extinctions," says lead author Erin Riordan. Riordan conducted the research as a postdoctoral scholar at the University of California, Los Angeles.

Some 5,300 plant species are native to California—more than any other state. About a third are considered rare, threatened, or endangered by the California Native Plant Society.

Sensitive plants "make up so much of our biodiversity, that if they're not doing well, we'll be losing a lot," Riordan says.

Riordan used sophisticated climate models to determine whether sensitive plants currently found at NRS reserves are likely to survive there in the future. She came to this work after completing her PhD at UC Los Angeles. For her dissertation, she modeled how climate change will affect the plants of southern California's coastal sage scrub.

"I wanted my research to have applications for conservation," Riordan says. "So when the opportunity to work with the reserve system came up, I thought this would be a great way to do this type of modeling in a way that could make a difference."

Protected lands such as the 39 reserves in the NRS are major bulwarks of conservation. Its wild landscapes ensure that native plants and animals will continue to find the open space they need to survive. Reserves include examples of most of California's major habitat types.

Safeguarding biodiversity

"As a microcosm of the state's ecological diversity, the NRS is a good surrogate for how sensitive plants will fare across the entire state," says Peggy Fiedler, executive director of the NRS. "This study shows not only how well the NRS safeguards plant biodiversity but also how land managers across California can cooperate to protect vulnerable species going forward."

Riordan began her study by identifying the sensitive plants located at reserves. She consulted reserve plant lists as well as location data from herbarium collections.

"The NRS pulls higher than its weight class in terms of protecting more rare plants than expected," Riordan says.

A statewide refuge

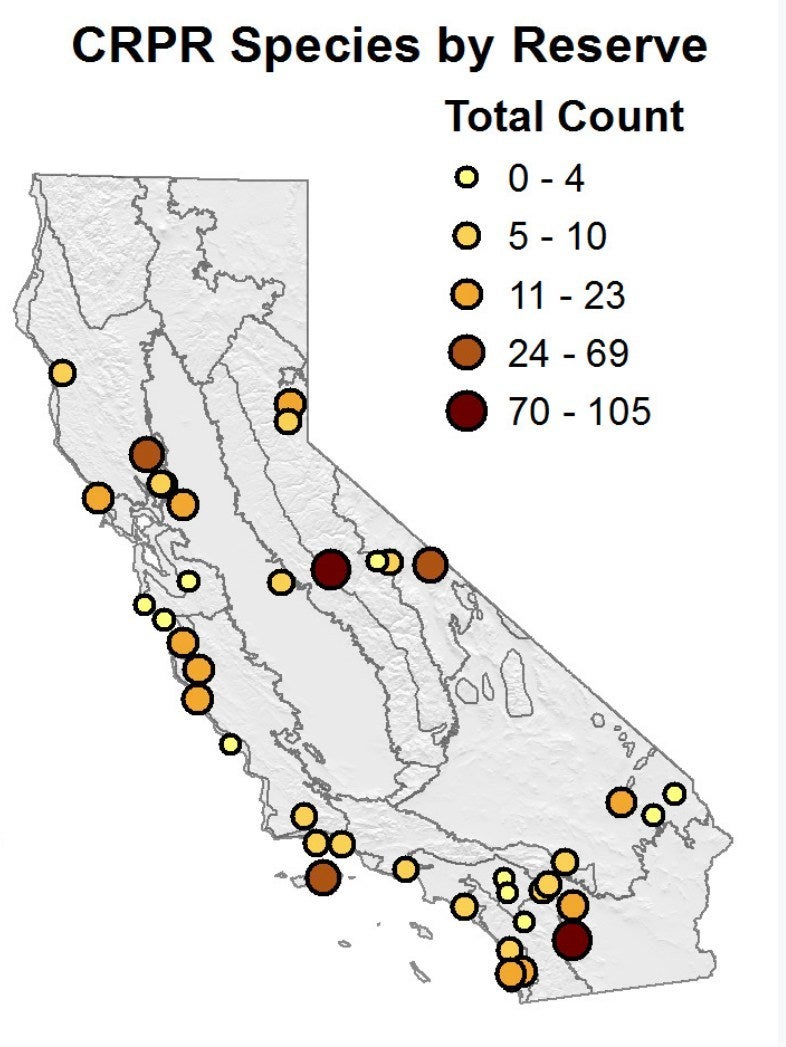

While the NRS covers less than one percent of California's land area, at least 16 percent of sensitive native plants, or 373 species, are found within its 756,000 acres. If anything, these numbers are likely an underestimate. Plant lists are often incomplete and surveys only find species that have sprouted in a given year.

"This finding underscores just how important the NRS is for conservation," Fiedler says. "We choose reserve sites in part for the significance of their habitats. These statistics demonstrate our reserves have been extremely effective at sheltering California's native plant species."

Furthermore, Riordan found, upwards of 70 percent of California's sensitive plant species have been recorded within 50 km (31 miles) of an NRS reserve or associated parks such as Yosemite.

What the models say

Riordan then used five different climate change scenarios to project what climate at reserves will look like by the end of the 21st century. Reserves in the Sierra Nevada and eastern California will warm far more than those along the coast.

How much rain and snow will fall is even more uncertain; predictions include both increased precipitation and increased drought. Overall, northern and central reserves may get wetter, while southern reserves may get drier. Even so, rising temperatures will increase the drought stress experienced by plants across the NRS.

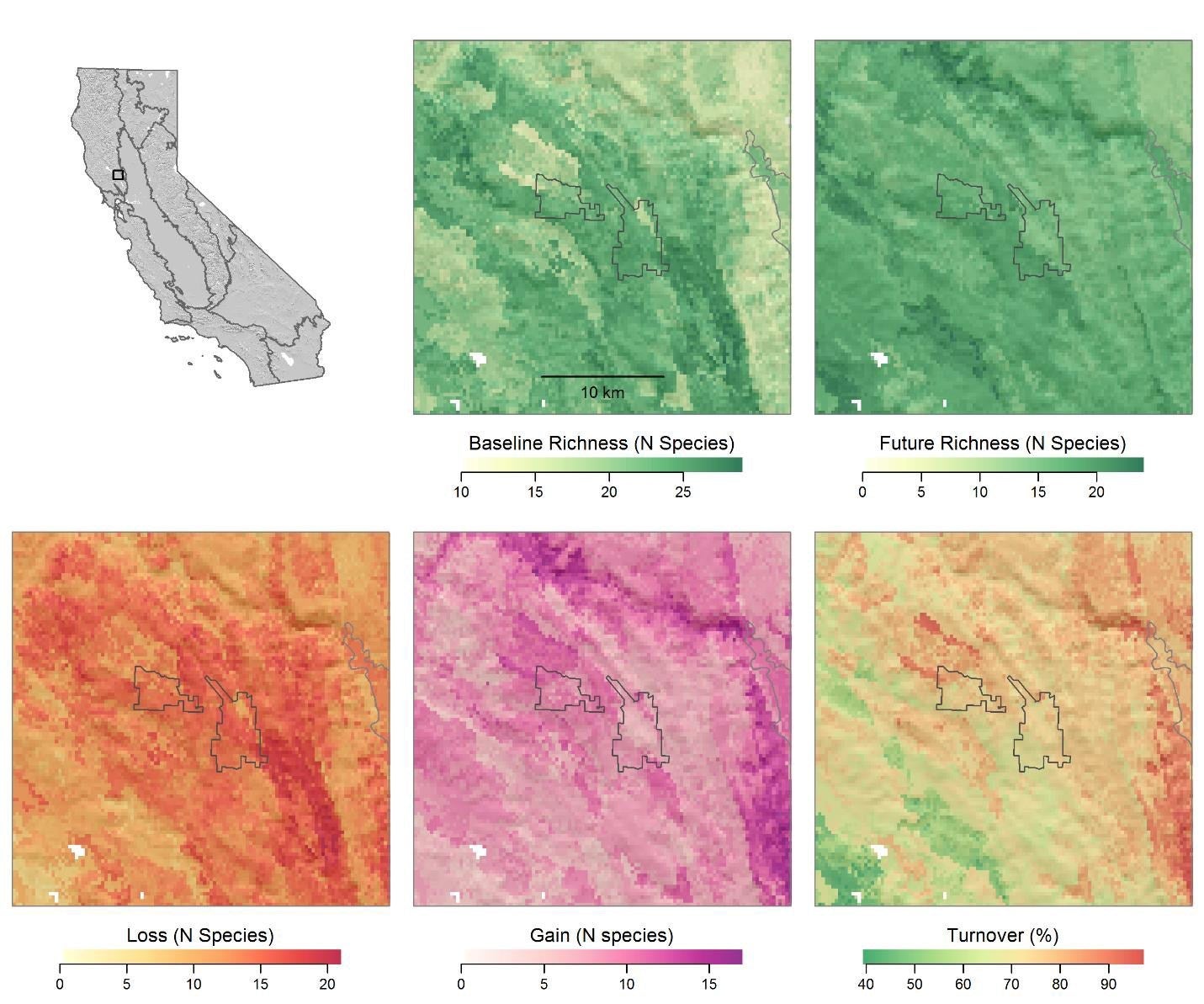

Riordan wanted to know how many sensitive plants now found within the NRS would need to relocate out of the system to find their growing conditions by 2100. She compared the moisture and temperature requirements for 180 sample species against where those climate conditions will be in the future.

This is where the study's findings got grim. Riordan found that more than half of these species would lose most of their habitat if they couldn't move beyond reserve boundaries.

"That right there is a conservation and resource management challenge," Riordan says.

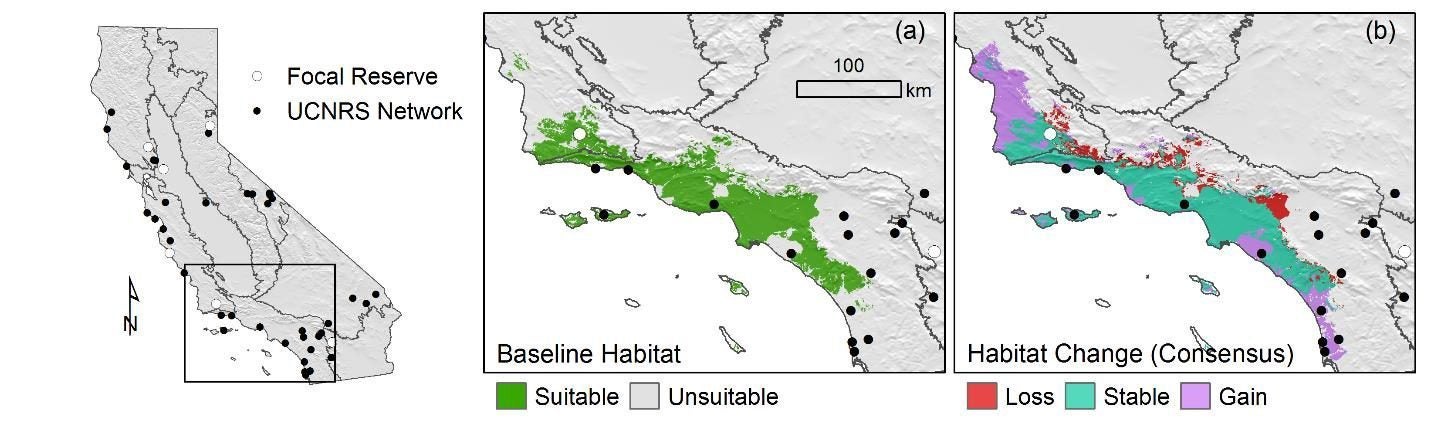

Riordan went on to evaluate how well six reserves representing a variety of locales and climates were able to retain their vulnerable plants. She found that under future climate scenarios, these reserves retained suitable habitat for less than half of sensitive plant species.

The migration dilemma

One solution is for plants to migrate. And indeed, the outcomes got rosier when Riordan assumed species could migrate to newly suitable habitat within the reserve system and adjacent protected lands such as Anza-Borrego Desert State Park.

But migration isn’t the quick fix it might seem. Genetic traits such as drought, heat, and cold resistance, as well as the availability and quality of newly suitable habitat, affect whether a species will be able to thrive in new environs.

Whether plants can reach suitable new sites is another question. Humans can certainly transplant specimens or carry seeds to new sites. Whether people should carry out such assisted migrations, however, is debatable.

“If we humans move plants too fast, too soon, we could disrupt the important local adaptation and genetic diversity that populations need to respond to changing conditions on their own. Or we could create populations no longer adapted to the current climate,” Riordan says.

Uncertainty about what future climate will look like at a given place complicates matters further. People could easily miscalculate and move plants to inappropriate new homes.

Collaborating for conservation

The NRS will be key to ensuring vulnerable plants persist into the future. For example, many reserves have long histories of scientific observations. Current reserve staff also tend to have a good sense of how species on their sites are faring.

"There's a wealth of institutional knowledge at reserves," Riordan says. "Our best strategies will incorporate tools like modeling with information from active scientific research and knowledge of that particular location," Riordan says.

In addition, many reserves are located next to large open spaces, and have strong relationships with other land management agencies. These connections help agencies, scientists, and other stakeholders work together to manage species at risk.

"There's a lot of room to develop management strategies to help ensure some of these really negative predictions are not what we wind up with," Riordan says. "The quicker we can work together to create these connected landscapes, the better shot we have at maintaining biodiversity and the important ecosystem services all of us rely on.”